That’s it. Barker: A Novel by Matthew Samuel Sweet–formerly titled Hitler, My Hero–is done. It’s available as a paperback and as an ebook on Amazon. Here’s the premise (in case you missed it):

“Demagogic professor James Barker is prevented from delivering a lecture series which appears to deify Adolf Hitler. In response to the censorship he abandons his tenure-track position at a renowned university and founds the Barker Alternative Institute of Learning.

Several years later, at the apex of its success as a cutting-edge online school, BAIL welcomes its first cohort of in-person attendees. BARKER follows three of these teenage students—Christopher, Alex and George—through their first weeks.

Orientating themselves in their new environment, forging relationships with fellow students and singular professors, and grappling with BAIL’s alternative curriculum are not the only challenges the trio face. James Barker’s ideas and methods make BAIL the target of activism and force the students to choose where their loyalties lie and whom they will stand by.”

And here’s the prologue, which is free-to-read. Just click here.

Now, one thing remains; a post-project review. This is that.

I’ll do it in three parts.

- PART ONE will evaluate the writing process involved in making Barker a reality. The respective phases I’ll look into are: preparation, research / ideation, outlining, drafting, macro-editing, micro-editing, and shipping.

- PART TWO will evaluate Barker as a finished product in accordance with the elements of its story: authorial intent, characters, world, events and narration.

- PART THREE will take a simpler form. I first came across it in reference to how military forces assess recent operations. It’s three simple questions: What was supposed to happen?, What actually happened? and What did I learn?

I’ll also riff a little outro / conclusion. Expect a few platitudes (sorry not sorry) and some insight into what I’m turning my hand(s) to in the immediate future. Simple enough, right? Let’s find out.

(Quick note: throughout this review I’ll refer to the book as Barker, even though it was called Hitler, My Hero until very late on. More on that here.)

PART ONE – THE WRITING PROCESS

This is my understanding of the writing process.

I’ll get to the different stages shortly, but just in case you are wondering what “thrashing” is… It’s a term from Seth Godin’s Linchpin. Short-hand, I think of it as things that can be changed without regressing the entirety of a project. Godin’s words provide a bit more context:

“Thrashing is essential. The question is: when to thrash?

In the typical amateur project, all the thrashing is near the end. The closer we get to shipping, the more people get involved, the more meetings we have, the more likely the CEO wants to be involved. And why not? What’s the point of getting involved early when you can’t see what’s already done and your work will probably be redone anyway?

The point of getting everyone involved early is simple: thrash late and you won’t ship. Thrash late and you introduce bugs. Professional creators thrash early. The closer the project gets to completion, the fewer people see it and the fewer changes are permitted.”

Make sense? Okay. Now, to the first stage of the writing process…

- Preparation

In my mind, this is everything that occurs before the official or unofficial start of a project. And given that I started Barker roughly two years ago, when I was twenty-six, I’ll think you’ll agree that here is not the place to include a multi-decade autobiography. Instead, I’ll try and describe the moment that Barker became a Thing.

As far as I can recall, it happened whilst reading William Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Its fourth page contains the following passage:

“A few moments later they witnessed the miracle. The man with the Charlie Chaplin mustache, who had been a down-and-out tramp in Vienna in his youth, an unknown soldier of World War I, a derelict in Munich in the first grim postwar days, the somewhat comical leader of the Beer Hall Putsch, this spellbinder who was not even German but Austrian, and who was only forty-three years old, had just been administered the oath as Chancellor of the German Reich.”

Couple the above observations with Hitler’s foreign policy triumphs, his wartime conquests, his promising but ultimately disastrous campaign in the East and his suicide alongside the love of his life in a besieged Berlin. What do you get? In my case, the following marginalia: Self-help, Hitler style.

I envisioned a parody of the archetypical rags-to-riches story with Herr Hitler as the protagonist. Further, I imagined the story told in a way that caused the reader not only to sympathise with Hitler, but to feel an authentic mixture of compassion and admiration for all that he was and all that he did.

That idea faded quickly, however. Not only did I not reckon myself a possessor of the wit and competence required to pull off such a parody, I sensed a deeper mystery. One that, to me, held greater appeal. What would happen if Hitler really was deified? How would our perception of Hitler’s words, thoughts and deeds change if we tore away the lenses of morality and propriety? More importantly, who would be capable of such a vision and why would he or she think it necessary or valuable to propagate it?

That, friends, was the moment that James Barker was born.

- Research / Ideation

The research / ideation stage is so titled because it involves driving towards answers to specific questions and the exploration of possibilities associated with numerous open-ended queries.

The fact that James Barker was an amoral trickster intent on releasing cognitive dissonance into the world raised other questions. Where would he teach and what platforms would he have at his disposal? How would a typical institution react to his ideas? How would the wider culture and various subcultures react to them? Say he was shunned; what would he do? If he founded his own school, how would it come about? Who would go there? What students would attend and who would make up the faculty? Where would the school be situated? What would it teach? Who, if anyone, would oppose its ambitions and methods? And behind all that, what would James Barker be trying to accomplish?

Answering all these questions led me down many rabbit holes. I’ll explain them in more detail in Part Two, but for now it suffices to say that I spent the better part of a year toying. I know this because the earliest Scrivener document I can find has a date of September 2017–right after I finished Shirer’s book. And it wasn’t until December 2018 (maybe a month or two before that) that I began to write Barker in earnest.

So, somewhere between September 2017 and the end of 2018, Barker became more than a possibility. It became a project and I started deliberately accumulating the ideas to fuel it.

- Outlining

The model of the writing process pictured above looks clean. Neat. Tidy. It isn’t. In reality, each stage bleeds into every other, either directly or indirectly.

For example, whilst assembling ideas about the curriculum for the Barker Alternative Institute of Learning, I mapped out the first semester of classes and where Barker’s Hitler, My Hero lecture series would fall within that. Naturally, that leant me a structure to build a story around. There are more instances I could cite, but generally the research / ideation phase formed the backend of the outlining phase.

There are some things that are very specific to the outlining stage, however. For example, Barker has twelve chapters (ignoring the Prologue and Epilogue). Why is that?

(Go ahead and guess…)

Answer: because Hitler’s Reich lasted for 12 years. This is also how I came up with word total targets for each chapter. The total number of days between Hitler’s assumption of the role of Chancellor and his death was 4,482. So, 12 chapters, each of 4,482 words, gave me a total word count of 53,784. Add a prologue and an epilogue (half a chapter apiece, so 2,241 words each) and the target for the novel as a whole was 58,266 words.

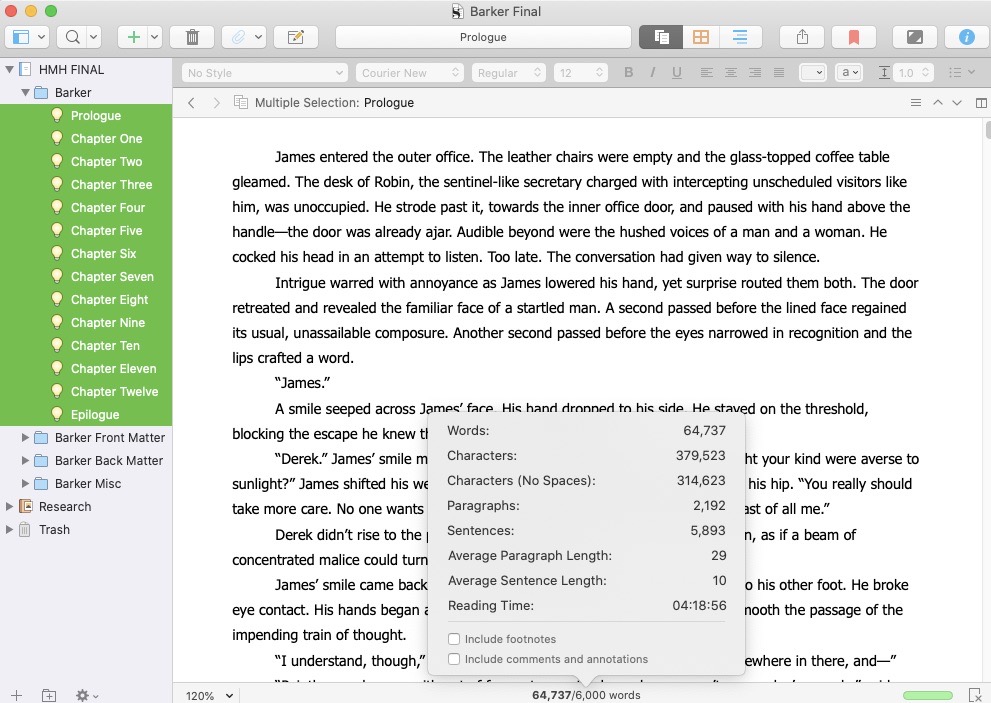

(Here’s what the end result was, by the way…)

This does seem kind of arbitrary. And it is, really. But the reason I did it is that, first, generally speaking, creativity loves constraints. Second, and more specifically, I thought that it was better to write a short debut novel than a longer one. Better for me, and for potential readers.

Continuing on with the constraints theme: I’d read Shawn Coyne’s The Story Grid and Robert McKee’s Story–alongside a slew of other books about writing and story. I knew I wanted structure in advance, that I wasn’t keen on winging it. Some people can work like that. I can’t. Both texts talked of a hierarchy of story “units”, which generally looks like this:

A story is composed of Acts. An Act is composed of Sequences. A Sequence is composed of Scenes. A Scene is composed of Beats. A Beat is composed of a change in a Value brought about by Conflict (- – to – to + to + +).

So, I had my twelve chapters, and my prologue and epilogue. That left two choices for splitting it into acts: three acts of four chapters, or four acts of three chapters. This is probably the point where I settled on the three viewpoints of Christopher, Alex and George, which meant I had a four-act story, with each act containing three chapters. This four-act structure isn’t made explicit in the book, but it is there.

Next up was the beats. If one chapter is 4,482 words, how many beats could I appropriately fit in? After a bit of digging, I decided a beat would be about 500 words. Running the math, I worked out each beat would be about 560 words and that there would be eight of them per chapter. Across the whole novel, that means 104 beats total. I began to outline.

I started with an idea of the story overall. I broke that down into four parts / statements, to represent the acts. Then I went into more detail and attempted to figure out what would happen in each of the chapters, again using a single-sentence summary. Once I had that, I broke it down into beats and did the same thing.

As you can probably guess, the idea of writing a novel becomes much easier when broken down like this. I just approached it beat-by-beat, aiming to get to a shitty first-draft with some rapidity, and then improvising from there.

- Drafting

On paper, the drafting looked simple. In practice, it presented many challenges. Deformities blossomed before my very eyes. I found gaps in my world-building, unresolved questions about the characters, I found that my conception of events didn’t work or was tortuous.

As I said above, the parts of the process mixed. I re-outlined. I revisited my old research and made new forays, coupled it with extra ideation. I looked up genre and tried to figure out where my novel would sit and what it would have to contain–this is also where I realised the importance of Christopher-Alex-George triangle and finally got a handle on the central conflicts in the story.

If I recall correctly, I think I went from beat-by-beat outline to rough first draft in about three to four months. Between December 2018 and April 2019 I finished the draft. I think it came in at 70,000+ words, a smooth 15,000 above my target.

I worked around my day-job, which involves shift-work, so I wasn’t writing every day. Instead I was writing for two or three days in a row, then working for two or three, then writing again. At the outset, I’d have thought this would have hindered me. But I think it actually boosted my performance. I couldn’t fully satiate my desire to write the story, so I went away a little hungry and came back every time with my energy intensified. That’s how it was through the entirety of this project.

Another thing I had to confront during the draft was point of view. I took a little time over that, reading up on the advantages and the disadvantages of different styles. Eventually I settled. I went for the third-person perspective, using the past tense, and decided the narrator would not be omniscient. I quite like stories where the reader knows more than the characters, however. Seeing the crash coming gives a nice flavour to experience. And because I was using three perspectives, I was able to do a bit of that whilst maintaining each character’s innocence and un-knowledge.

Something else: voice. As I got through beat after beat, something like a style began to emerge. I wouldn’t say the prose was flowery, but I did find myself being a tad extravagant. I was liberal with metaphors, happy to freeze time and explore the thoughts contained within a character’s mind at a particular moment. This is one of the great things about story for me–the chance to see what is otherwise missed in reality.

That being said, I didn’t want to be too literary–that’s the best word I can think of, and I don’t mean it as a slur or a derogatory term. For me, the story was the focus, not the way it was told. So, alongside the reflective paragraphs and the expanded thoughts, I tried to be direct, to the point. I tried to offer concrete, forensic descriptions.

In Partial pictures and imprisonment, I came up with this 2×2:

I understand the value of empty prose. More importantly, I like it. That’s why I held back on descriptions after a character had been introduced. I wanted the reader’s imagination to take over after the initial contact. In such a landscape little things can have large importance. That’s why there is mention of hand movements, of hips twisting, of a flicker or frown of the lips. I scattered these like seeds, hoping they would enrich the reader’s own already-existing picture.

- Macro-Editing

The whole time I was drafting, I was also macro-editing. To me, macro-editing is concerned with story structure. It is distinct from micro-editing, which I see as line edits, issues of grammar and word choice. You know, the nuts and bolts. Macro-editing, in contrast, is about the broad strokes.

As I drafted I macro-edited. Some things worked. A lot of things in the story didn’t. For most of this process, I relied on intuition and an understanding of my intent. Naturally, that made the process inefficient and the progress hard-to-yield. But after a few months of back-and-forth the story began to improve. This was the tail-end of 2019.

A comment on endings: The initial ending I planned was violent. Think lynching plus burning. I wrote it and liked it, in and of itself. But upon reflection I thought it overkill. My inhibition wasn’t with the content, per se, but more with its appropriateness to the story as a whole. I revised it majorly but the alternative ending came out limp, boring. The initial ending had big, heavy, over-bearing fangs. The alt had nowt but gums.

- Micro-Editing

At the end of October 2019–with my “Finished by 2020” deadline fast approaching–I sent the Prologue out to beta-readers. They provided their thoughts; I made changes and sent a revised copy; they made further comments; I polished it up and either marked it as done or put it online. I repeated this process for most of the chapters. It was incredibly helpful. Barker was made many, many times better thanks to their input.

Looking back, I averaged about a chapter or two each month. It was slow going for me and at this point I began to micro-edit too, focusing on the story at the sentence-by-sentence level. After interactions with the beta-readers, I run each chapter through software called Autocrit. It helped me with the micro-edits and proved a boon.

However, after about Chapter Seven or Eight fatigue set in. I was being less rigorous with the edits and the re-drafts. My desire to see the thing done was catching up to my desire to do the thing well. In the later chapters, I let things slide that I wouldn’t have in the earlier chapters, earlier in the process. One easy example of this is the chapter lengths. The later chapters are shorter than the early chapters. On balance, I think it worked out okay. But I could have done so much more. The ending, which I rewrote a third time, was sufficient but I know it could’ve been much more of a showpiece.

This troubled me so much because I knew it was happening. I thought long and hard about it. On one hand, I didn’t want to put out something shit. On the other hand, I reasoned that I’d improve more as a writer by doing more projects than by spending more time on a single one. I upped the pace and learned to deal with the unease.

- Shipping.

End of April 2020, I was done. Ready to go to print. I self-published, so what that meant was getting InDesign and Photoshop and putting the book together.

The exterior was simple. I’d come across the image I wanted on Unsplash in October 2019. I didn’t want to fork out for an illustrator / designer so I did some hunting for good typography covers and figured out what I wanted. I kept it simple.

The interior was more difficult. For my previous book, I used Word. It was a nightmare. My first encounter with InDesign also wasn’t pleasant. One afternoon, I got in a huff and went back to Word. That was worse. I came back another day and learned the basics of InDesign. Eventually, I made sense of it and it actually turned out to be quite fun.

I opted for the smallest stock size for the book (5×8 inches). That was my basis. Then I leafed through some fiction books on my shelf and considered the setup of the body text, as well as the front and back matter. A week or three before my InDesign foray, I came across Butterick’s Practical Typography via an Andy Matuschak thread on “web books”. To say it was a God-send would be correct. Without that, the book would look a lot worse than it does.

I went through a couple iterations, but the book-as-a-product materialised rapidly. About a month and a half from start to finish of production.

I’ve already mentioned how much the beta-readers contributed. I wanted to do something in kind for them so I grayscaled the planned cover and uploaded it. I ordered a box of them and once they were dispatched I changed the cover to the colour edition. There’s twenty grayscale editions of Barker and each beta-reader will get one. It’s not much, but it’s something.

Also worth noting is the complete absence of marketing associated with the book. The reason I didn’t take the route of finding an agent and pitching a publisher was that I didn’t want to waste time persuading people to give me a shot. I wanted to write it, not persuade people to let me write it. (In part I also think I wasn’t that confident about the idea early on.) I felt the same about marketing, really. Time spent marketing was time not spent writing.

I don’t know how I feel about this now, to be honest. On one hand, the lack of marketing infrastructure is painfully obvious. On the other hand, it takes a long-term concerted effort to build an audience or a platform and I wasn’t ready to commit to that. I don’t even know if I am now. I recognise that I have to do something alongside writing more books, but what that is and what that looks like in concert with the rest of my life, I don’t know. I’ll continue to think on it.

INTERLUDE

I think the above gives a fairly detailed look into the writing process that resulted in Barker. Questions and requests for further clarifications are welcome, though. Anywho, let’s surge ahead with Part Two.

PART TWO – THE ELEMENTS

There are five elements to a story:

- Authorial Intent: Potency and purity of vision.

- Character: The cast of beings.

- World: The universe the cast inhabits.

- Events: What happens to the cast.

- Narration: How the above is described.

We’ll take them in the listed order…

- Authorial Intent

In this post I said:

“In my mind, authorial intent is something akin to Proust’s “reflecting power”, but it includes something different, too. Authorial intent is a quality whose potency is felt on some non-conscious level by an audience member. It has to do with the purity of an executed vision. It is what makes a seemingly mediocre story—in terms of it characters, world, events and narration—strike right through to the soul. Its absence is what makes a story with incredible characters, an immersive world, an ingenious plot and deft narration feel limp and lifeless on a deep level.”

So, the question is: Does Barker have it? I’d love to hear what you think. Personally, I think it does. To a degree. Barker is not as potent as the masterpieces of world literature. It also doesn’t have that aching intensity that I’ve felt whilst reading other works of fiction and non-fiction which are derivative of times of great suffering or profound joy for the author. And I certainly didn’t crank Barker out without feeling, thought, compassion or care. It occupies a middle ground.

I’m watching a documentary series called The Last Dance at the moment. I’d like to say that Barker has flashes of potential, like one might get a glimpse of during a rookie’s first season. There’s quality, sure, but it’s not fully developed yet. Not proven. I may seem like a bit of an ass for saying that. Ah well.

- Character

Barker has four primary / viewpoint characters: James Barker, Christopher, Alex and George. It has eight secondary characters: Mary, Arty, Henrik, Charles and Isabella Bard, Linda and Turner. It also has a slew of tertiary characters. There was one secondary character called “Jackson” who got cut from the ending. For each of the primary and secondary characters I filled out the following profile (this is LONG):

CHARACTER PROFILE

BASIC

Name:

Age/DOB:

Nationality:

Socioeconomic Level as a Child:

Socioeconomic Level as an Adult:

Hometown:

Current Residence:

Occupation:

Income (Actual/Percentile):

Talents/Skills (Top 5):

–

–

–

–

–

Significant Experiences:

–

–

–

–

–

Birth Order:

Siblings (describe relationship):

Spouse (describe relationship):

Children (describe relationship):

Grandparents (describe relationship):

Grandchildren (describe relationship):

Parents:

Significant Others (describe relationship):

Relationship skills:

PHYSICAL

Height:

Weight:

Race:

Eye Colour:

Hair Colour and Style:

Glasses/Lenses:

Skin Colour:

Shape of Face:

Distinguishing Features:

Body Shape?

How Does He/She Dress?

How Does He/She move?

Describe the following:

- Eyes:

- Nose:

- Mouth:

- Hair:

- Chin:

- Hands:

- Torso:

- Arms:

- Legs:

- Feet:

- Head Shape:

- Hips:

- Shoulders:

- Posture:

Mannerisms:

Habits:

Health:

Hobbies:

Favourite Sayings:

Speech patterns:

Disabilities:

Style (Elegant, Shabby etc.):

Greatest Flaw (Perceived):

Best Quality (Perceived):

Greatest Flaw (Actual):

Best Quality (Actual):

PSYCHOLOGICAL

Educational Background:

Intelligence Level:

Any Mental Illnesses?

Learning Experiences:

Character’s Short-Term Goals:

Character’s Long-Term Goals:

How Does Character See Himself/Herself?

How Does Character Believe He/She is Perceived by Others?

How Self-Confident is the Character?

Ruled by emotion or logic or some combination thereof?

What would most embarrass this character?

EMOTIONAL

Introvert or Extrovert?

How does the character deal with anger?

With sadness?

With conflict?

With change?

With loss?

What does the character want out of life?

What would the character like to change in his/her life?

What motivates this character?

What frightens this character?

What makes this character happy?

Is the character judgemental of others?

Is the character generous or stingy?

Is the character generally polite or rude?

SPIRITUAL/PHILOSOPHY

Does the character believe in God?

What are the character’s spiritual beliefs?

Is religion or spirituality a part of this character’s life?

…

NARRATIVE ROLE & RELATIONSHIPS

Classification (Primary, Secondary, Tertiary):

How the Character is Involved in the Story:

Character’s role in the novel:

Scene where character first appears:

Relationships with other characters:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Character differences/transition; beginning vs end?

MISC

Myers-Briggs profile?

Jungian archetype?

Character align with or break any well-established tropes?

D&D Alignment:

Appolonian or Dionysian?

What does he carry and why (how does he/she own it) (in the VGR sense)?

Part One – Every Day Carry

Part Two – Week Long Trip Abroad

Similarity to real-life or fictional characters:

–

–

–

–

–

SCENARIOS/SKETCHES/SANDBOXES

Relative to the world, describe how the character handles/performs/acts in the following scenarios (be rigorous and excruciatingly detailed):

- Waking up

- Going to the toilet

- Brushing teeth

- Getting dressed

- Eating breakfast

- Moving through their house

- Interacting with a friend

- Interacting with a colleague

- Interacting with a stranger

- Interacting with an enemy/adversary

- When left alone in a room, without stimulation

- Walking in the cold and rain

- Performing a monotonous task

- Their favourite activity

- Talking on the phone to a family member

- Lying in bed, unable to sleep

- Lost an item of importance

- Confronted with a beggar, or someone seeking charity of some kind

- Playing with an animal

- Tidying a room or part of their house

- Showering

- Writing in a notebook

- Tasked with an impossible puzzle

- Physical discomfort/pain/suffering

- On crowded public transport

- In a museum or awe-inspiring structure (like a cathedral)

- Sat by a river

- Having a prank played on them

ADDITIONAL NOTES?

IMAGES AND LIKENESSES

I filled out of most of this for each of the primary and secondary characters. The one thing that remained aspirational was the “scenarios/sketches/sandboxes”. I let them blank as a last resort, in case I couldn’t get the essence of a character. Still the process was fun. I won’t share all the profiles but here are some tidbits from the four primary characters.

- James Barker

This is my answer to, “How does he move?”

“With a learnt confidence. His gestures and body language are not so much artificial as deliberate. The use of his hands when he talks, the impassiveness of his face, the tilt of his head, the calm measured movements of his limbs; these are choices which accent the impression he wishes to give off. They lend him a certain unhumanity, a reptilian cast to his regard (think K’chain Che Malle) Nevertheless, the excitement and raw curiosity still seeps out. When he is emotionally invested (which is usually only when he is intellectually immersed/engaged) his calm, deliberate demeanour falls apart. He shifts from foot to foot, his gestures rise up and outwards, his hands move faster, the tempo of his steps increase. His eyes, rather than seeming to look past you, look into you, past your assumptions and seem to go right down into your very being. Thus, he flits between a clammed-up, reserved, high status demeanour, and an intense, unbridled, overwhelming attentiveness.”

I pegged five characters / people he was similar to: Richard Feynman, Eliezer Yudkowsky, Jack Sparrow, The Joker, and Jordan Peterson.

- Christopher

Re-reading his profile, I realise he ended up a lot more confident, a lot more outgoing than originally planned. The ideal I had in mind for him was the “innocent kid” and early on that came out as shyness. In the end, he was still the innocent kid, but he had a natural charisma, a confidence, a sincere curiosity and drive to question.

- Alex

Fun-fact: I did initially plan to write Alex in such a way that the reader would be unable to pinpoint her gender. I gave up on that (because it would be hard) and made her female.

If Christopher was the innocent kid, she was the social justice warrior. Hailing from an affluent family, Alex wants to be “a change agent, someone who makes a difference on a global scale”, so her short-term goal is “to accumulate as much experience and as many contacts as poss. to set herself up for future contribution.” Why? Because Alex “sees herself as someone gifted by circumstance, and in a position to help others.”

Her transition from the start of the story to the end?

“In the beginning, she is naive, thinking that change can be brought about by relentless, tireless activism. She thinks good intentions are good enough, and that global change comes through global initiatives. In the end, she realises that actions have higher order, unintended consequences, and that society and its occupants are parts of a complex system which is hard to steer, monitor, adapt, change. In short, some of her air of certainty and purpose is replaced with doubt, and with her a scaling down of her schemes.”

- George

George was one of the darkest, most cynical characters. Easy to see why. I mean, I had him growing up in the Deep South. And I gave him these “significant experiences”:

– Father humiliated by a black man, and he witnessed it (nature of humiliation?) (minor incident but magnified in his mind)

– Learning of past eminence (family fallen from grace via takedown of slavery?)

– Eclipsed consistently by those with healthier/better dispositions, which drives him further into cynicism and cruelty.

– Discovering the dark pleasure he gains in other’s failure, humiliation, pain etc., esp. Those who seem successful etc (better than him in certain ways)

– Overshadowed by older brother in every arena (physicality, sports, education, affection from family)

– Constant illness as a young child left him somewhat estranged from his classmates and feeling like a burden to his parents

– Seeing his mother’s meekness in response to his father’s domination/imposing-ness

– Denied interest from the opposite sex as too hostile a personality, won’t let them get close

– Being made to feel like an outsider (no friends, no clubs or communities or groups)

– Growing up in the shadow of his brother and father and grandfather has made him feel like he is the runt of the family.

These are the relationship skills I allocated him:

“Minimal. Due to illness growing up, and to self-imposed and externally imposed isolation, he lets no one close, and when he does, it is only as a ruse to set up a later betrayal or cross. Cynicism very much excludes possibility of deep and intimate relationships, unless those people share his malevolent streak, and then there is a relationship inspired by a savage, animal like joy.”

Dude didn’t stand a chance. None of them did, really. But one thing I will note is that I watered the original profiles down in the end. Their traits–explicit and intense according to their profiles–became more subtle, softer, a bit more malleable. That doesn’t change the fact that I set them up to conflict. Alex’s social activism and ambitions were meant to contrast with Christopher’s innocence and George’s cruel cynicism. It’s interesting to note that my original characterisations were quite trope-y / stereotyped.

Another thing I did whilst creating the characters was grab headshots for each of them. Henrik looked like Brock Lesnar; James Barker was modelled on Richard Feynman, but made a bit leaner; I imagined Mary as Rosa Parks-esque. For Christopher, Alex, George and the others, I used backstage.com’s “find talent” to look through headshots and find ones that fit the character. I came back to these surprisingly often, especially when I was stuck with a character’s actions in a certain scene.

- World

Creating characters is fun because it’s so easy. You kinda just start the ball rolling and let your imagination do the rest. Having explicit details to gather makes it easier, too. World-building is a different kind of fun. I had this Breaking Smart newsletter in mind, which charts some ways in which imagination and nerve can fail or be weak. I was determined not to let that happen with my world-building.

My world-building had three main components: the Barker Alternative Institute of Learning, the Hitler, My Hero course and the clandestine groups involved in protesting the former.

1) BAIL.

I wanted to give BAIL a gloss of real-world vigour. Early on, I considered sending off a pitch to Y Combinator to see if the concept actually had legs. I didn’t do that. But I did spec out BAIL in some detail. For example, here’s its historical development:

“Stage 1 (0-2 years, content-era): Began as a series of online lectures (new as well as re-purposed) from a changing core of individuals which were distributed for free, on a third-party platform.

Stage 2 (2-3 years, context-era): The courses, which originally were randomly released and distributed, began to become more structured and come with more support material, and the lectures themselves began to take the shape of a curriculum, intertwining with one another yet standing on their own, and being hosted primarily on their own self-supported platform, whilst still made available elsewhere.

Stage 3 (3-5 years, community-era A): After the optimisation of the substance and style (of both content and distribution) an increasingly vigorous interaction between creators and audience was established. This resulted in the piloting and adoption of a paid-for level/tier. The content remained the same, but what differed were exclusive interactions with the lecture creators and a discussion/community network moderated for value-add dialogue and commentary.

Stage 4 (5+ years, community-era B): Previously, the lectures from disparate individuals and the community that developed around them was sheltered under the name of James Barker. At this stage, Barker sounded out Mary X to help him create an in-person institute—Barker Alternative Institute of Learning. She came on board. They then began to look for a suitable location, figure out the tiered structure, work out the structure of curriculum, and choose their mission and its execution.”

And here is the application process for BAIL’s in-person offering:

“…announcement of BAIL IP program via Barker’s already established platform. Applications opened to all tier members simultaneously. The application has generic elements and novel ones, but is centred on specific biases. Specifically, BAIL IP students are preferred to be between 18-20 (post high school , pre-college), have records that demonstrate significant personal initiative (via projects etc) outside of regular finite games, show ambition/aspirations outside the normie sphere, demonstrate novel methods of thought and perception, and be pre-disposed to emergent activity (be it pub/pri, async or async), and if possible, be legacy members of BAIL tiers/curriculum with established stream smarts, or if not, have begun to accumulate stream smarts in other domains/groups. Judgement made irrelevant of gender/ethnicity/socioeconomic status etc. It also deliberately disregards eloquence, favouring selection via evaluation of taken actions instead of described ones (doers > talkers). Whether any of this is the case is determined by a long (~ 1 year from closing date to final acceptance) series of applications, sync/async tasks and interviews which become progressively more intense in length and duration as the field of applicants is slimmed/culled/narrowed by attrition.”

And this paragraph explains how BAIL ended up with its own particular atmosphere:

“The five core classes qualify as “rhizomatic” topics, and are thus immune to traditional meta-learning approaches (top-down and bottom-up; see Rhizomatic Meta-Learning series). Thus, they require adventurous teachers capable of transporting equally (or more) adventurous students from any point in the rhizome to any other, utilising abstraction/synthesising leaps, analytical dives and shapeshifting as necessary (see The Rhizome Traveller for more details). Online, this means the death of traditional, canned performances (a la TED) which preserve the fourth wall, and the uprising of live and interactive explorations which unite and bind the audience and the actor together and feed off the reciprocal and escalating energy in realtime. Offline, this means each professor comes prepared, less with notes than with the requisite experience, understanding and expertise which enables them to manoeuvre with supreme majesty, and also with the necessary confidence/lack of inhibition that allows them to improvise authoritatively and in an engaging manner.”

On the whole, I think BAIL is a good approximation of a school environment, even if it is a bit eccentric.

2) The Hitler, My Hero course.

This was tricky. I knew the book would be based around this so I didn’t want to just hand-wave it. After deciding on six themes (politics, culture, race, military, organisation and logistics, and Hitler himself) I had intended to assemble notes / scripts and work directly from them when it came to the appropriate chapters. I didn’t do that.

Instead, when I got to the relevant chapters, I basically drafted the talk / course in-situ, based on what I read and how I thought Barker would proceed from one topic to the next. Naturally, I ended up with gaps which I had to go back, revise and fill. But I think it turned out okay.

3) Clandestine groups.

I won’t go into too much detail here, as it is too close to the story. But I did think about this in some depth. For the groups, I created notes on the following:

- Management, manipulation and circumvention of the boundary between lawful/unlawful action.

- Campaign and org information discoverable by parties with different levels of interest/involvement.

- Avoidance of law enforcement, surveillance and counter-measures.

- Selection of targets (algorithms, observers and informers).

- Core activities and ambitions, basic plays and escalations.

- Pitching, co-ordinating and conducting different levels of campaigns (incl. examples).

- Need vs greed dichotomy, freedom from and freedom to.

- Bringing people in, kicking people out, and organisational/operational roles.

- Fringe vs mainstream focus?

- Generations of warfare tactics (1st to 5th and features/bugs).

- Funding methods and revenue distribution.

- The action against Barker/BAIL.

- Distribution of info regarding local and global active campaigns.

- Composition and activities of typical counter-balancing forces/organisations/opposition.

- On the greater cultural instability (1/2/3/4th world) and the ingress of the Fourth World.

- Inaction/action thresholds, observers and informers.

The notes assembled allowed me to (I hope) create a fictional organisation that seemed to possess real power and evoke real menace in the story’s world.

- Events and Narration

I think I covered the basic specifics in Part One, so I’ll give an overall comment instead. Narration-wise, I’m basically content with how Barker turned out. For a first run out the blocks, I don’t think I could have done much better. Not without the addition of an experienced editor, anyway.

Event-wise, I think Barker would have been improved had the story’s timeline been extended and had the scale of events been allowed to escalate. As it stands, the novel covers a relatively thin slice of that alternate reality. Were I, for some inexplicable reason, to lose all the archived work I have and be compelled to re-write it again, I’d up the ante across the board.

PART THREE – THREE QUESTIONS

Three simple questions; two simple answers and one not-so-simple answer…

What was supposed to happen?

I was supposed to write a short, thrilling, suspense-full novel centred around the themes of censorship and cultural conflict, and release it by the end of 2020.

What actually happened?

I wrote a short, less-exhilarating-and-more-literary than planned novel about coming-of-age in the midst of cultural conflict, and released it in June 2020.

What did I learn?

Tl;dr: A lot. But the biggest takeaway?

Concerning the writing process, I think the biggest takeaway was the relative difficulty of drafting versus editing. I imagined that drafting would be hard, a slog. I’ve seen the takes and the memes about Writing Life, about how it’s such a struggle. It didn’t turn out that way. Everything up until I had a full working draft was fun. Everything after that was still fun, but there was a lot more difficulty and challenge in the mix.

Concerning the elements, my biggest takeaway was the interdependence. This whole thing would be much easier if each individual element could be isolated and trouble-shot. But it just doesn’t go that way. Messing with one element is like messing with a complex ecosystem; there’s unexpected effects, feedback loops, catastrophes, unexpected boons. This makes the tinkering process a great source of aliveness and a great sink of time, emotion and energy.

BOOSTED

Overall, this project has had a simple effect; it’s given me a boost. It’s imparted a confidence, a momentum, that I can carry into other projects. It sounds simple but doing something relatively difficult for the first time unlocks so many more possibilities.

Three, four, five years ago, if you’d have told me I’d be writing fiction I’d have told you to GTFO. Funny how the present twists and contorts to create futures we never imagined, isn’t it? Makes me wonder what’s on the horizon, right now. For me, there’s definitely more writing. Fiction and non-fiction. Outside of that? I have no idea yet I’m excited to find out.