A user’s interaction with a product can be imagined as a continuous experience. Like linguistics, genetics and computing, a product can be viewed as a one-dimensional thing.

Product management involves, chiefly, manipulating the line and managing its legibility. Line legibility is the task of making a product’s lines comprehensible to others; interfacing with and integrating inputs from stakeholders from business, engineering, design, sales and marketing, operations and so on. Line manipulation involves, for the most part, discretisation of the product line and the addition of dimensionality to its singular dimension.

This discretisation and dimensionality-buffing are both “arbitrary” in the hard science sense—not meaningless, just something that is required to enable the larger product operation to actually function—and they are the core of common line management activities, such as:

- User research programmes

- Systematic product discovery

- Technical diagramming and modelling

- Experience architectures, flows and journeys

- Funnel construction and throughput optimisation

- Cross-functional teaming and autonomy distribution

- Sprints and other progressively tighter iterative engineering delivery cycles

In this post I’m ignoring the utilisation of dimensionality and its interplay with product lines. The focus is on the push and pull of discretisation and continuousness. Specifically, I want to look at how cycling between conceptions of continuous and discrete product lines powers value creation.

Consider the following, which is the canonical continuous-discrete dynamic for a product line:

- Original, continuous

- Original, discretised

- Modified, discretised

- Modified, continuous

Of particular interest are two key transformations:

- The outer transformation: an original, continuous line to a modified, continuous line

- The inner transformation: an original, discretised line to a modified, discretised line

The inner and outer transformations that can occur are constrained by the line’s sole dimension. Fortunately, there are only so many ways a line can be transformed.

For the outer transformation—one continuous line to another—the possibilities are:

- Length change: the line becomes longer or shorter

- Friction change: it takes more or less resource to traverse the line

- Displacement: the line is subverted entirely and wholly replaced

Length change is easy to conceptualise. The experience of a product can be stretched or shrunk. Friction change is similarly simple. A one-click buy versus a multi-stage journey, for example. Displacement is a little trickier. It can be thought of as abstraction and/or encapsulation. Of course, each of these changes may be independent or they may occur in parallel. And each subset of change may or may not create value for the end user.

The possibilities of the inner transformation—one discretised line to another—are more abundant. Imagine a line discretised into ten pieces. For each of those pieces, there may be a change in the length or friction. There may also be a complete displacement. Additionally there may also be a division, an explosion of the original discrete step into children. These four operations—length or friction change, displacement, division—may take place:

- On all of the discretised elements in different combinations

- On some of the discretised elements in different combinations

- On one of the discretised elements in different combinations

Alas, the simple continuous-discrete-discrete-continuous transformation yields much possibility.

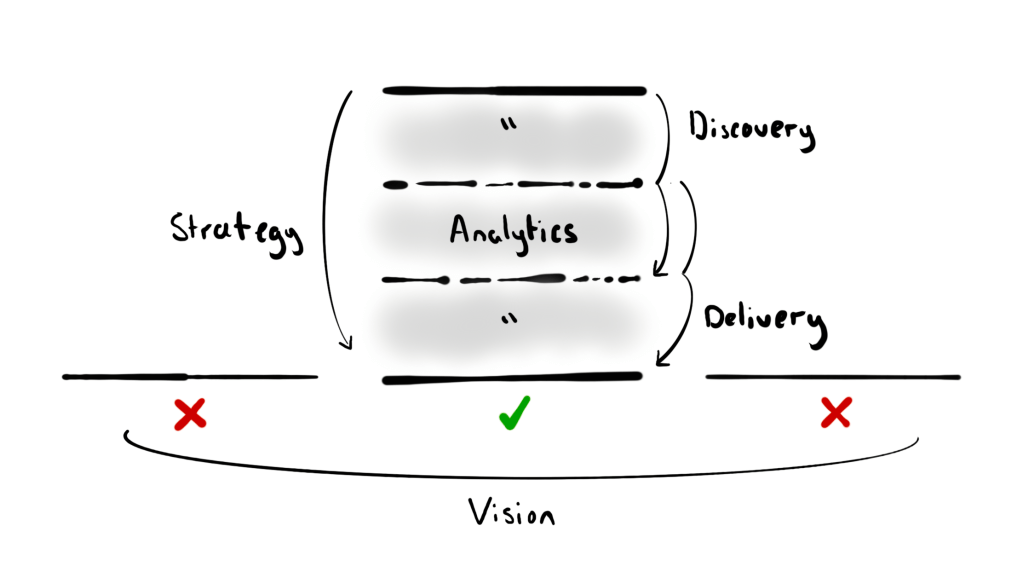

Another lens for interrogating this canonical continuous-discrete dynamic? The diagrammatic. See: the strategic theory of John Boyd and one of its oft-cited components; the OODA loop. See: the visualised structures of viable systems theory and cybernetics. See: the following sketch:

The relationships between the four canonical stages—original continuous, original discrete etc.—encompass product vision, strategy, discovery, delivery and analytics:

- Product vision: choosing one of many possible modified, continuous lines as a horizon

- Product strategy: transitioning from the original, continuous to the modified, continuous line

- Product discovery: discretising the original, continuous line and assessing options for the modified, discretised line

- Product delivery: executing the original to modified discretised line transition, and translating the modified discretised to the modified, continuous line

- Product analytics: analysing the respective zones between the four canonical lines

Lines; transformations; operations; relationships—all these constitute yet another useful fiction for the puzzle that is product management. A generalised structure, sure, but one that offers a different way of seeing.