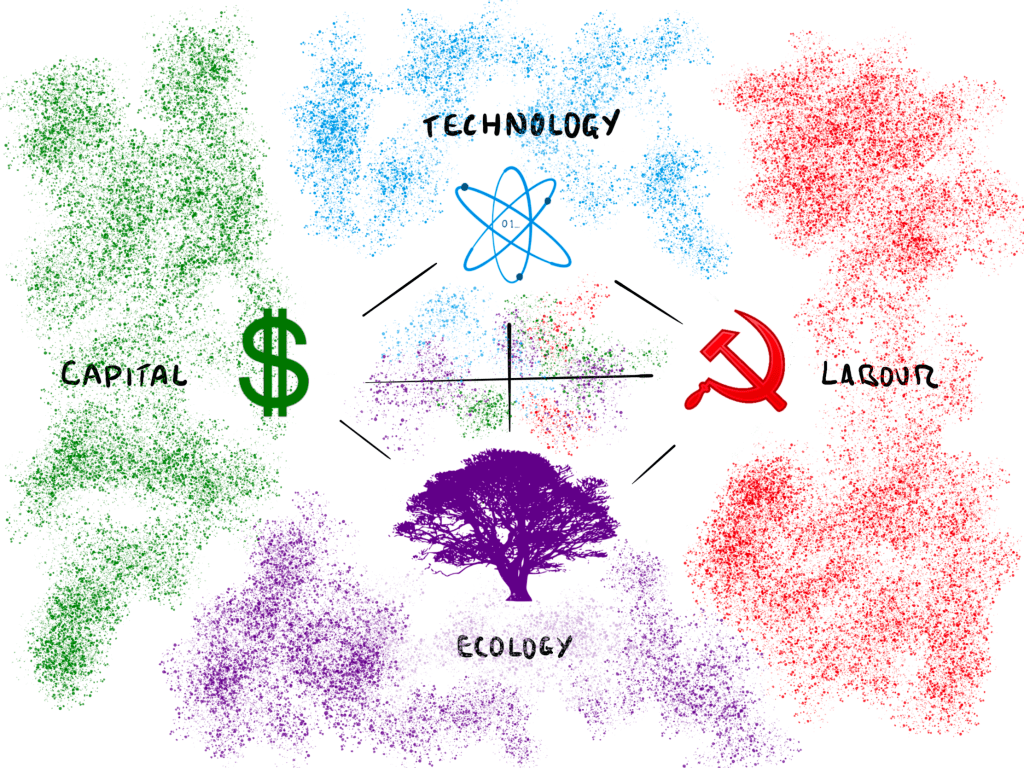

In the last year I’ve made a deliberate effort to listen to podcasts. This consumption is typically tethered to activities that require low cognitive engagement —chores, meal prep or clean-up, driving, playing with the dogs when it’s too wet to walk. Like my reading—where I have “tracks” to guide engagement—I’ve structured my consumption. The three themes (not including basketball and health/fitness) that emerged? Capital, technology and labour. These are somewhat juxtaposed and designed to introduce dissonance. To perturb the attractors of my thought. For example, one of the earliest trio of podcasts was:

- Acquired (capital): “Learn the playbooks that built the world’s greatest companies — and how you can apply them as a founder, operator, or investor.”

- Zero Knowledge (technology): “…a weekly show which goes deep into zk and the decentralised web. We interview top technical minds building new systems and tech on emerging networks. Through these conversations, we hope to uncover future paradigms that change the way we interact — and transact — with one another online.”

- Tech Won’t Save Us (labour): “Every Thursday, Paris Marx speaks to a new expert to dissect the tech industry, the powerful people at its helm, and the products and services it unleashes on the world. They challenge the notion that tech alone can drive our world forward by showing that separating tech from politics has consequences for everyone, especially the most vulnerable.”

The intent is not so much to ensure a balanced perspective—like the BBC’s much maligned doctrine of impartiality—but to create un-balance, to unsettle assumptions, to invoke divergent thought, to surface the malleability of one’s own representations of reality.

I think this structure is doing the intended work. And even if it is not it’s turning out to be fun. If I were to take it further I would look for maximal divergence amongst the prongs. Perhaps, pitting the A16Z podcast alongside Working People and Titans of Nuclear. I haven’t done that yet, but I do stick to the capital-tech-labour split in spirit when I update my listening stack and add in a new show.

What I realised recently, however, is that this trio has utility outside of the attentional bracing it provides for media consumption. To see how, let’s increase the resolution by providing some verbose definitions for each of the trio:

- Capital: distilled, discrete units of liquid, agentic potential as represented by assets and resources with mutual, agreed upon value.

- Technology: the evolving collection of natural phenomena captured within an assemblage of socio-technical systems and practices that allows a civilisation to fulfil diverse purposes.

- Labour: the purposeful and systematic conversion of energy and matter into forms of progressively higher complexity and meaning undertaken by organic agents.

With just those definitions, one has a compact useful fiction for analysing systems and dynamics. Foreground one of those at the expense of the others during a portrayal and one has an interestingly skewed lens for what’s going on, and why.

For example, the birth of a startup could be narrativised as risk-laden intellectual labour that catalyses a technological innovation that itself beckons capital. The interpersonal dynamics that unfold as that same startup goes from innovation to product to organisation could be understood as interactions between agents of capital (e.g. a VC), agents of technology (e.g. the CTO), and agents of labour (e.g. an arbitrary, low-level employee).

Another way to utilise the trio? As an iron triangle (the pick-2-of-3 version, not the US policy version). Some societies or cultures that embody the possibilities (enumerated by ChatGPT)?

- Tech-labour: “Ancient Egypt had a strong emphasis on technology and labour. They developed advanced architectural techniques like the construction of the pyramids, which required advanced engineering knowledge and a significant labour force. The society also developed technologies for agriculture, medicine, and other purposes, all of which were intricately tied to the labour force.”

- Capital-tech: “Silicon Valley in California, USA, is a prime example of a culture that emphasises capital and technology. It is known for its concentration of technology companies and venture capital firms. The culture in Silicon Valley revolves around innovation, entrepreneurship, and the rapid development and adoption of new technologies. Capital investment plays a crucial role in driving technological advancements in this region.”

- Labour-capital: “Feudal societies in medieval Europe placed a strong emphasis on labour and capital. The feudal system was built on the labour of serfs who worked the land owned by the nobility (capital owners). Land, which was a form of capital, was the basis of power and wealth in this society. The labour of the peasants and serfs was essential for agricultural production, which supported the entire system.”

Instead of the “pick two” directive, one could also use a “plus two” directive. These are again described by ChatGPT:

- Technology plus labour: “When individuals or collectives apply technology, utilising their knowledge and competencies, to systematically convert energy and matter into more intricate and meaningful forms (labour), they have the potential to create products, services, or innovations of value. This value generation can result in the accumulation of assets and resources, collectively recognised as capital.”

- Capital plus technology: “When capital is invested in acquiring or implementing technology, it frequently leads to the establishment of systems and practices that augment productivity and efficiency. Consequently, this can create opportunities for labour, as more efficient processes and technologies often necessitate human agents for operation, maintenance, or further refinement.”

- Labour plus capital: “When individuals or collectives partake in labour endeavours, they may generate innovations or enhancements to existing technology and practices. Moreover, the aggregation of capital resources can be channelled into research and development initiatives aimed at advancing technology. As labour and capital resources are allocated to enhance and create new technologies, this synergy can lead to the continuous progression of technology.”

Yet another way to leverage the trio is to Procrustes the three into Rene Girard’s concept of mimetic, triangular desire. Here’s a ChatGPT-supplied summary of the key components:

“Imitation: Girard’s theory begins with the premise that humans are fundamentally imitative creatures. People imitate the desires, behaviors, and even preferences of others, especially those they admire or perceive as models. This imitation is not limited to superficial behaviors but can extend to deeper desires and aspirations.

Rivalry: As individuals imitate others, they may also begin to desire the same objects or goals as the people they imitate. This can lead to rivalry, where individuals compete for the same resources or the same desired outcomes. Girard argues that rivalry is a natural consequence of mimetic desire.

Mediation: In a mimetic desire context, individuals often desire the same things as others, and this shared desire leads to a triangular dynamic. The object of desire becomes a mediator between the individuals, serving as a focal point that intensifies the competition or conflict. This triangular structure is what Girard refers to as triangular desire.

Conflict and Violence: Girard’s theory suggests that mimetic desire and rivalry can escalate to the point of conflict, competition, and even violence, as individuals become more and more consumed by their shared desires and the struggle to obtain the desired object. This can have profound implications for social relationships and even entire societies.

Scapegoating and Sacrifice: Girard also explores the role of scapegoating and sacrifice in resolving mimetic conflicts. He suggests that societies often manage mimetic tensions by directing collective aggression toward a scapegoat, blaming them for the social turmoil and then sacrificing or ostracizing them. This process temporarily alleviates the conflict but does not address the underlying mimetic nature of human desires.”

Through this lens, the juvenile taunts and roasts that sail back and forth between tech and media elites takes on a new meaning—their joint desire to capture the boons of technology is what mediates their yapping.

Similarly, if we rotate the trio and place, say, technology at the peak, then a cultural analysis of how agents of labour and agents of capital both strive to become more tech-like becomes available. More interestingly, one of the central tenets of Girardian theory is that religion subverts mimetic desire and the inevitable escalation of violence by making God the focal point. I’ll leave you to speculate which of the three—capital, technology or labour—is most suited to serve as such a Godhead.

Now, for one final manipulation of the trio. Interactions between the three forces of capital, technology and labour do not happen in isolation. They are embedded within the confines of a larger context, an enveloping environ, a fourth force:

- Ecology: the integrated, agent-rich, multi-scale generation, flow, interaction, transformation and dissipation of energy and matter that occurs within the spacetime-bound locus of a sufficiently large terrain.

All the intertwingling that occurs between capital, technology and labour is governed by the constraints of the surrounding ecology and, more importantly, either nurtures, sustains or degrades the present and future civilisational hypercomplexity it is able to embody.